11/20/2024

Some unknown theorems that blow my mind away

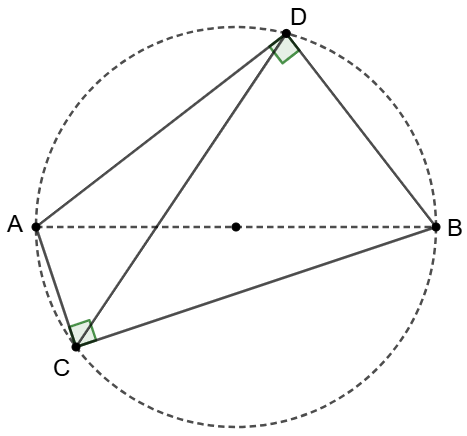

Chord length and diameter:

\(\begin{multline}

\shoveleft \dfrac{CD}{sin\angle{CBD}}=\dfrac{BC}{sin\angle{BDC}}=\dfrac{BC}{sin\angle{BAC}}=\dfrac{BC}{BC/AB}=AB\\

\shoveleft \implies CD=ABsin\angle{CBD}=ABsin\angle{CAD}\\

\shoveleft \text{The length of a chord (CD) equals the diameter (AB) times the sine of the angle}\\

\shoveleft \text{formed by its endpoints and any point on the circle}

\end{multline}\)

\(\begin{multline}

\shoveleft \dfrac{CD}{sin\angle{CBD}}=\dfrac{BC}{sin\angle{BDC}}=\dfrac{BC}{sin\angle{BAC}}=\dfrac{BC}{BC/AB}=AB\\

\shoveleft \implies CD=ABsin\angle{CBD}=ABsin\angle{CAD}\\

\shoveleft \text{The length of a chord (CD) equals the diameter (AB) times the sine of the angle}\\

\shoveleft \text{formed by its endpoints and any point on the circle}

\end{multline}\)

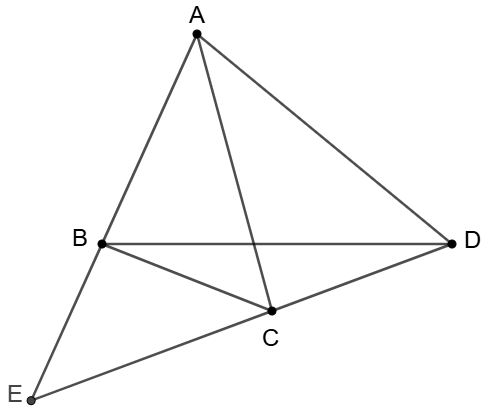

Sine of triangle sides

\(\begin{multline}

\shoveleft \dfrac{sin\angle{ADC}}{AE}=\dfrac{sin\angle{AED}}{AD} \implies sin\angle{ADC}=\dfrac{AE}{AD}sin\angle{AED}\\

\shoveleft \dfrac{sin\angle{CDB}}{BE}=\dfrac{sin\angle{AED}}{BD} \implies sin\angle{CDB}=\dfrac{BE}{BD}sin\angle{AED}\\

\shoveleft \implies \dfrac{sin\angle{ADC}}{sin\angle{CDB}}=\dfrac{AE \cdot BD}{BE \cdot AD}

\end{multline}\)

Note: this fraction is often used in Ceva’s Theorem in trigonometric form.

\(\begin{multline}

\shoveleft \dfrac{sin\angle{ADC}}{AE}=\dfrac{sin\angle{AED}}{AD} \implies sin\angle{ADC}=\dfrac{AE}{AD}sin\angle{AED}\\

\shoveleft \dfrac{sin\angle{CDB}}{BE}=\dfrac{sin\angle{AED}}{BD} \implies sin\angle{CDB}=\dfrac{BE}{BD}sin\angle{AED}\\

\shoveleft \implies \dfrac{sin\angle{ADC}}{sin\angle{CDB}}=\dfrac{AE \cdot BD}{BE \cdot AD}

\end{multline}\)

Note: this fraction is often used in Ceva’s Theorem in trigonometric form.

07/02/2024

There is a series of 6-post writing on AOPS community blog containing quite a lot lemmas and conclusions. The posts just list them out without the details on proving. Also there are some related docs on Evan Chen’s page which can be listed here too:

At the end of above PDF, an AOPS forum link is mentioned about some other handouts:

- Collected Muricaaaaaaa PDF and its solution

04/26/2023

Here are some of the tips I got when I started teaching primary math using AOPS books:

-

For arithmatic and algebraic calculation, always do simplication like cancel as early as possible, and do multiplication as late as possible. Factorized numbers is better than a single number during calculation.

-

$\dfrac{a}{b} = \dfrac{c}{d} \implies ad=bc$. This trick should be taught as early as possible to save a lot of calculation work.

-

After getting solutions of an equation, always check them. You can easily bring new solutions to an equation like $x^2+x+1=0 \implies x + 1 + \dfrac{1}{x} = 0, 1 + x = -x^2 \implies x^2 = \dfrac{1}{x} \implies x^3=1 \implies x=1, x=\dfrac{-1 \pm \sqrt{3}i}{2}$. By checking the solutions, we know that $x=1$ should be excluded.

04/01/2021

I.M. Gelfand quotes:

It was not our intention that all of the students who study from these books or even completed the School by Correspondence should choose mathematics as their future career. Nevertheless, no matter what they would later choose, the results of this mathematical training remain with them. For many, this is a first experience in bing able to do something completely independently of a teacher.

I would like to make one comment here. Some of my American colleagues have been explained to me that American students are not really accustomed to thinking and working hard, and for this reason we must make the material as attractive as possible. Permit me to not completely agree with this opinion. From my long experience with young students all over the world, I know that they are curious and inquisitive and I believe that if they have some clear material presented in a simple form, they will prefer this to all artificial means of attracting their attention - much as one buys books for their content and not for their dazzling jacket designs that engage only for the moment. The most important thing a student can get from the study of mathematics is the attainment of a higher intellectual level.

reading

07/25/2021

The area $K$ of cyclic quadrilateral whose sides have lengths $a,b,c,d$ is

$K=\sqrt{(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)(s-d)}, s=\dfrac{a+b+c+d}{2}$

03/07/2021

Geometry - Topology book list

Geometry

There are various English-language editions of Euclid available at archive.org. Search here.

Euclidean

Introductory

- Euclid, tr. Heath. The Elements. Dover. (Vol I / Books 1-2, Vol II / Books 3-9, Vol III / Books 10-13)

- Euclid, tr. Heath. The Elements Green Lion Press. (Single volume)

-

Euclid books 1-6, tr. Byrne. This one is neat because the diagrams have colors. Archive.org links: link 1 Link 2 Link 3 - Lang and Murrow. Geometry: A High School Course (2e, Solutions manual)

- Kiselev and Givental. Kiselev’s Geometry (Vol I: Sumizdat 1e; Vol II: Sumizdat 1e) - Look for seller “sumizdat_dot_org”, that’s the publisher.

- Coxeter. Introduction to Geometry (Wiley 2e, 2e HC [OOP])

- Birkhoff and Beatley. Basic Geometry (AMS Chelsea ed, At AMS store; Manual for Teachers [at AMS store], Manual for Teachers [at AbeBooks]; Answer book [at AMS store], Answer Book [at AbeBooks])

- Brannan, Esplen, Gray. Geometry (2014, ISBN 978-1118679197, Worldcat, Amazon)

- Meyer. Geometry and Its Applications (2e, 2006: ISBN 978-0123694270, Worldcat, Amazon)

- Augros. The Arts of Liberty, Introductory Geometry and Arithmetic. (Web page, PDF)

- Harpur. 1894 interpretation of Euclid.

- Africk, Elementary College Geometry. This is a typewritten, hand-illustrated text. It introduces two-dimensional geometry, with a focus on finding numerical solutions rather than proving theorems.

- Lozanovski, A Beautiful Journey Through Olympiad Geometry. Free PDF, form asks for information before downloading.

Beyond introductory

- Coxeter. Geometry Revisited (MAA 1967)

- Johnson. Advanced Euclidean Geometry (Dover)

- Casey, 1886. A Sequel to the First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid (At archive.org)

- Altshiller-Court. College Geometry: An Introduction to the Modern Geometry of the Triangle and the Circle (2e Dover)

- Coxeter. Regular Polytopes (3e)

- Petrunin. Euclidean plane and its relatives; a minimalist introduction - covers elementary geometry and beyond, assumes knowledge up to basic calculus

Euclidean and non-euclidean

- Hartshorne. Geometry: Euclid and Beyond (1e)

- Moise. Elementary Geometry From An Advanced Viewpoint (3e, 2e)

- Greenberg. Euclidean And Non-Euclidean Geometries (4e)

- Coxeter. Non-Euclidean Geometry (6e)

- Hilbert and Cohn-Vossen. Geometry and the Imagination (AMS Chelsea)

- Leonard, Lewis, Liu, Tokarsky. Classical Geometry: Euclidean, Transformational, Inversive, and Projective (1e 1997: ISBN 978-0760706602, Amazon; 2e 2003: ISBN 978-1592441303, Amazon)

- Stillwell. Numbers and Geometry (1e, 1997: ISBN 978-0387982892, Worldcat, Amazon)

- Stillwell. The Four Pillars of Geometry (1e 2005: ISBN 978-0387255309, Worldcat, Amazon)

- McDaniel. Geometry by Construction: Object Creation and Problem-solving in Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries

Focusing on projective geometry

- Coxeter. Projective Geometry (2e)

- Cremona, 1885. Elements Of Projective Geometry (At archive.org)

- Meserve. Fundamental Concepts of Geometry (Dover)

- Veblen and Young. Projective Geometry (At archive.org: Vol 1, Vol 2, Search)

Computational Geometry

- de Berg, Cheong, van Kreveld, Overmars. Computational Geometry: Algorithms and Applications (3e)

- Edelsbrunner. A Short Course in Computational Geometry and Topology (1e)

- O’Rourke. Computational Geometry in C (2e)

- Cheng, Dey, Shewchuk. Delaunay Mesh Generation (1e)

- Botsch, Kobbelt, Pauly, Alliez, Levy. Polygon Mesh Processing Hardcover (1e)

General Topology

-

Munkres. Topology (2e intl, 2e)

The standard text. Also includes basic algebraic topology.

-

Mendelson. Introduction to Topology (3e Dover)

A brief introduction, available cheap.

-

Gamelin and Greene. Introduction to Topology (2e Dover)

Another cheap alternative. One of Alan Hatcher’s recommendations.

-

Crossley. Essential Topology (1e corr)

An introductory text with a reputation for easy reading.

-

Willard. General Topology (Dover)

Another affordable introduction. Maybe too much information for a true first book.

-

Jänich. Topology (1e)

Another of Alan Hatcher’s recommendations, he calls it “a pleasure to read.”

-

Kelley. General Topology (At Archive.org, Springer hardcover 1975, Ishi Press 2008, Van Nostrand 1955)

The classic introduction (1955).

-

Simmons. Introduction to Topology and Modern Analysis (Krieger 2003)

-

Croom. Principles of Topology (Dover)

A gentle introduction for beginners.

-

Prasolov. Intuitive Topology (1e)

An extremely gentle introduction for extreme beginners.

-

Steen and Seebach. Counterexamples in Topology (Dover)

-

Henle. A Combinatorial Introduction to Topology

Goes straight into algebraic topology with minimal coverage of point-set topology.

Algebraic Topology

- Hatcher. Algebraic Topology (f) (CUP Paperback, FREE ONLINE)

- Bredon. Topology and Geometry (1e)

- Stillwell. Classical Topology and Combinatorial Group Theory (2e)

- Rotman. An Introduction to Algebraic Topology (1e)

- Fulton. Algebraic Topology: A First Course (1e)

- May. A Concise Course in Algebraic Topology (1e)

- May and Ponto. More Concise Algebraic Topology: Localization, Completion, and Model Categories (1e)

- Lee. Introduction to Topological Manifolds (2e)

Differential Geometry

- Pressley. Elementary Differential Geometry (2e/2010)

- Tu. An Introduction to Manifolds (2e/2011)

- Guillemin and Pollack. Differential Topology (AMS Chelsea)

- Millman and Parker. Elements of Differential Geometry (1e)

- O’Neill. Elementary Differential Geometry (2e)

- Milnor. Topology from the Differentiable Viewpoint (PUP revised)

- Kreyszig. Differential Geometry (Dover)

- Spivak. A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry (in 6 volumes) (Vol I, 3e; Vol II, 3e; etc.)

- Guggenheimer. Differential Geometry (Dover)

- Bishop & Goldberg. Tensor Analysis on Manifolds (Dover)

- Lee. Introduction to Smooth Manifolds (1e)

- Lee. Riemannian Manifolds: An Introduction to Curvature (1e)

- Do Carmo. Riemannian Geometry (1e)

- Do Carmo. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces (2e Dover, 1e)

- Matsumoto. An Introduction to Morse Theory (1e)

- Kosinski. Differential Manifolds (Dover)

- Lovelock and Rund. Tensors, Differential Forms, and Variational Principles (Dover)

- Struik. Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry (Dover)

- McInerney. First Steps in Differential Geometry: Riemannian, Contact, Symplectic

- Tapp. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces

Applied and Computational Topology

- Ghrist. Elementary Applied Topology (At CreateSpace, At Amazon)

- Edelsbrunner and Harer. Computational Topology: An Introduction (1e)

- Zomorodian. Topology for Computing (1e)

- Kaczynski, Mischaikow, Mrozek. Computational Homology (1e)

Algebraic geometry

Introductions

- Beltrametti, Carletti, Gallarati, Bragadin. Lectures on Curves, Surfaces and Projective Varieties (1e)

- Garrity et al. Algebraic Geometry: A Problem Solving Approach (1e)

- Shafarevich, Reid. Basic Algebraic Geometry 1: Varieties in Projective Space (3e)

- Shafarevich, Reid. Basic Algebraic Geometry 2: Schemes and Complex Manifolds (3e)

- Holme. A Royal Road to Algebraic Geometry (1e)

- Fulton. Algebraic Curves, an Introduction to Algebraic Geometry

- Gathmann. Algebraic Geometry (SS 2014)

- Smith, 2014. Introduction to Algebraic Geometry (1e Paperback, FREE ONLINE)

- Vakil. The Rising Sea: Foundations Of Algebraic Geometry Notes (main page, blog, Ravi Vakil’s homepage)

Classical (pre-Grothendieck)

- Lang, 1958. Introduction to Algebraic Geometry (Martino)

- Weil, 1946, 1962. Foundations of algebraic geometry ()

- Lefschetz, 1953. Algebraic Geometry (Dover)

- Hodge and Pedoe, 1947. Methods of Algebraic Geometry (Vol I, Vol II, Vol III)

- Baker, 1922-1925. Principles of Geometry (At archive.org: Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5, Vol 6)

Beyond

- Hartshorne. Algebraic Geometry (1e)

- Liu. Algebraic Geometry and Arithmetic Curves (1e

- Griffiths, Harris. Principles of Algebraic Geometry (Intl ed @AbeBooks)

- Görtz, Wedhorn. Algebraic Geometry I, Schemes with Examples and Exercises (1e)

- Vakil. The Rising Sea: Foundations Of Algebraic Geometry Notes

- Eisenbud and Harris. 3264 and All That: A Second Course in Algebraic Geometry (1e)

03/03/2021

Pascal’s Theorem

Reference:

03/02/2021

Shoelace Theorem

Suppose the polygon $P$ has vertices $(a_1, b_1), (a_2, b_2),…(a_n, b_n)$ listed in clockwise order. Then the area of $P$ is

\[\begin{align*} S_P = \dfrac{1}{2} \left| (a_1b_2 + a_2b_3 + ... + a_nb_1)-(b_1a_2 + b_2a_3 + ... + b_na_1) \right| = \dfrac{1}{2} \left| \displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{n}{(x_{i+1}+x_i)(y_{i+1}-y_i)} \right| = \dfrac{1}{2} \left| \displaystyle\sum_{i=1}^{n}{det \left( \begin{vmatrix}x_i & x_{i+1} \\ y_i & y_{i+1}\end{vmatrix} \right)} \right| \end{align*}\]Reference:

02/26/2021

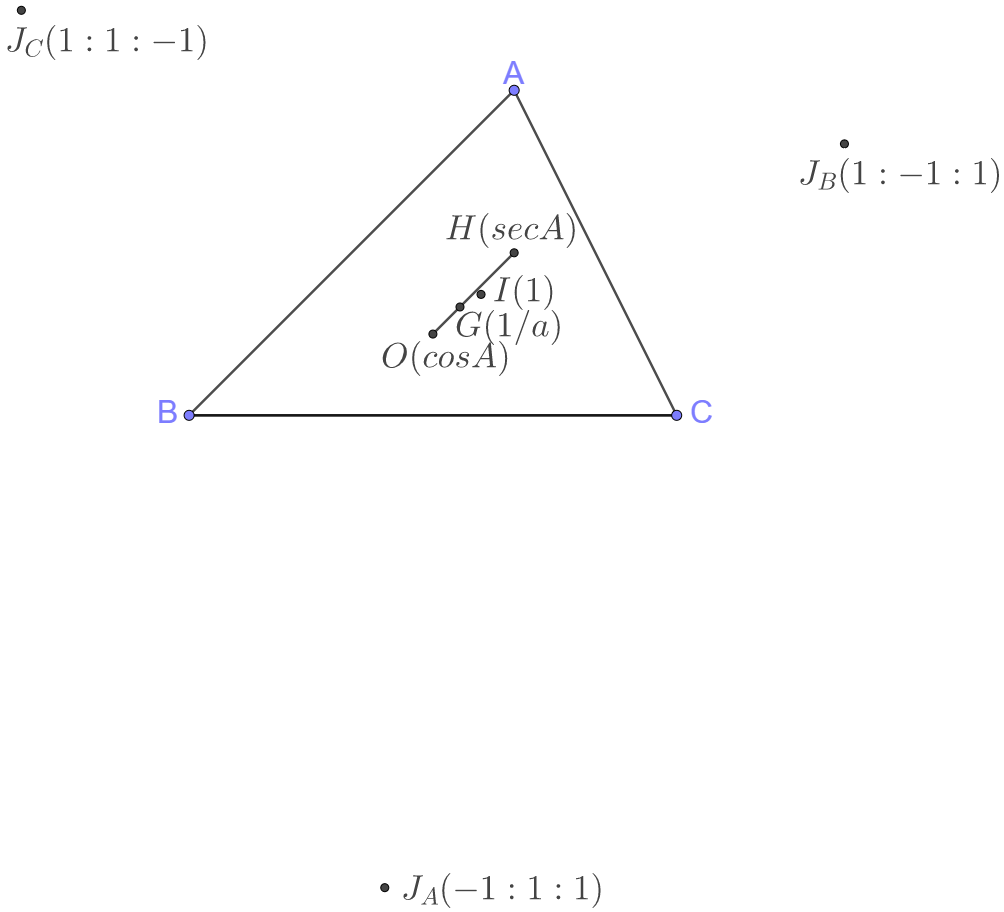

Trilinear coordinates and Barycentric coordinates

| Trilinear Coordinates | Barycentric Coordinates | |

|---|---|---|

| $A$ | $1 : 0 : 0$ | $a : 0 : 0$ |

| $B$ | $0 : 1 : 0$ | $0 : b : 0$ |

| $C$ | $0 : 0 : 1$ | $0 : 0 : c$ |

| $Incenter(I)$ | $1 : 1 : 1$ | $a : b : c$ |

| $Centroid(G)$ | $\dfrac{1}{a} : \dfrac{1}{b} : \dfrac{1}{c}=bc : ac : ab=cscA : cscB : cscC$ | $1 : 1 : 1$ |

| $Circumcenter(O)$ | $cosA : cosB : cosC$ | $sin2A : sin2B : sin2C$ |

| $Orthocenter(H)$ | $secA : secB : secC$ | $tanA : tanB : tanC$ |

| $Nine-Point \text{ }Center(N)$ | $cos(B-C) : cos(C-A) : cos(A-B)$ | |

| $Symmedian \text{ } Point(S)$ | $a : b : c = sinA : sinB : sinC$ | $a^2 : b^2 : c^2$ |

| $A-Excenter(J_A)$ | $-1 : 1 : 1$ | $-a : b : c$ |

| $B-Excenter(J_B)$ | $1 : -1 : 1$ | $a : -b : c$ |

| $C-Excenter(J_C)$ | $1 : 1 : -1$ | $a : b : -c$ |

-

The equation of points on the line $P=(p : q : r)$ and $Q=(u : v : w)$ is:

\[\begin{align*} \begin{vmatrix} p & q & r\\ u & v & w\\ x & y & z \end{vmatrix} = 0 \end{align*}\] -

The point with trilinear coordinate $(p:q:r)$ has the value $p, q, r$ being the actual perpendicular distances to the sides $a, b, c$ satisfy

\[pa+qb+rc=2S_{\triangle{ABC}}\] -

EFFT(Evan’s Favorite Forgotten Trick): Consider displacement vectors $\overrightarrow{MN}=(x_1 : y_1 : z_1)$ and $\overrightarrow{PQ}=(x_2 : y_2 : z_2)$. Then $MN \perp PQ$ iff $0=a^2(y_1z_2+y_2z_1)+b^2(x_1z_2+x_2z_1)+c^2(x_1y_2+x_2y_1)$

-

The area of a triangle with vertices $P=(x_1 : y_1 : z_1), Q=(x_2 : y_2 : z_2) and R=(x_3 : y_3 : z_3)$ is

- First Collinearity Criteria: The points $P=(x_1 : y_1 : z_1), Q=(x_2 : y_2 : z_2) and R=(x_3 : y_3 : z_3)$ are collinear iff

- When the coordinates are normalized, points $P=(x_1 : y_1 : z_1), Q=(x_2 : y_2 : z_2) and R=(x_3 : y_3 : z_3)$ are collinear iff

- The equation of a line through the points $P=(x_1 : y_1 : z_1)$ and $Q=(x_2 : y_2 : z_2)$ is

02/09/2021

The Erdős–Szekeres Theorem

This is a great proof for The Erdős–Szekeres Theorem, and it introduces a subfield extremal combinatorics by the book “Extremal Combinatorics with applications in Computer Science” by Stasys Jukna.

01/04/2021

Note: this is a quote from some webpage which may be hard to get now:

A Coin Problem

BY GARY ANTONICK MARCH 17, 2014 12:00 PM

This week’s puzzle was suggested by Daniel Finkel of the Seattle-based Math for Love. Our last few from Dr. Finkel traced the path of a traveling nun; this week we transition to new territory with a coin challenge. Here’s Dr. Finkel with —

A Coin Problem

One of my greatest math experiences came during a test. The test was for entry into the Hampshire College Summer Studies in Mathematics, a program for high school students that I credit with opening the door of mathematical beauty for me. They call it the Interesting Test.

I had three hours to take the Interesting Test, and it consisted of four, extraordinary questions. I’ve returned to them many times over the years. (One I already posted as a Numberplay Puzzle: What Color Was the Bear). But this one is special to me. I spent two of the three hours of the test working on this problem, and I never got a satisfactory answer. I returned to it and discussed it with others for years afterward. Over that time, I got more and more out of the problem.

Here’s the surprise, though: there is a slick, two-sentence solution that, once you know it, seems ridiculously obvious. And yet, it was precisely because I did not know or stumble on the “obvious” answer that I got so much out of the problem. This problem taught me how not knowing can lead to understanding.

So here is the challenge:

Consider this simple game: flip a fair coin twice. You win if you get two heads, and lose otherwise. It’s not hard to calculate that the chances of winning are 1/4.

Your challenge is to design a game, using only a fair coin, that you have a 1/3 chance of winning.

And here is my recipe for getting the most out of this problem: if you can solve it, do not stop with one answer. Rather, see how many answers you can come up with. I’ve posed this problem to many people, and I continue to hear novel solutions.

For Math Lovers in Seattle

If you are in Seattle this Saturday, March 22, join Daniel Finkel and his Math for Love teammate Katherine Cook at Seattle’s third annual Julia Robinson Festival! The mission of the Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival is to inspire students to explore the richness and beauty of mathematics through activities that encourage collaborative, creative problem-solving. Entry is by donation but advance registration is required. Click here to register your 4th-12th grader for the festival.

That concludes week’s challenge. As always, use Gary Hewitt’s Enhancer for an optimal Numberplay experience. And send your favorite puzzles to Gary.

Solution

Here’s Dr. Finkel with the complete solution and recap:

This is Dan with the solution to this week’s puzzle. Solutions, I should say, since commenters offered a slew of answers to this week’s problem. This “official” solution will be my reckoning of reader solutions, and what they show us about this problem.

Do-over Solutions

Here is Duncan Gilles (#3): “You essentially need to generate a 3 outcome game from a game that can only possibly have 2^n outcomes. So you’ll have to remove some of the outcomes. Here’s my way:

Flip the coin twice. If you get two heads, you win, if you get heads-tails or tails-heads, you lose. If you get two tails, you play again.”

Duncan Gilles put a finger on the difficulty hiding in this problem: any game that ends within some definite number of coin flips—say, n flips—has 2^n outcomes, and there is no whole number that can go in the numerator of a fraction when 2^n is in the denominator so that the fraction reduces to 1/3. The “do-over” solution, which relies on calling for a do-over if some option comes up, gives us control over the number of possible options. The cost is that the game could last a long time, if we were unlucky enough to flip tails for millions of flips in a row. But since the chances are ridiculously small that this could ever happen, it’s not too steep a price. In any case, it is a price that must be paid.

Readers contributed many variations on the do-over solution. Here are two I liked from one poster.

Kurt #25

“1) Flip 3 coins, sequentially. 2) If you get 0 heads or 0 tails, it’s a do-over. 3) The only remaining outcomes are 1 head (2 tails) or 1 tail (2 heads). 4) If the single head or tail is first, you win! 5) If the single head or tail is second or third, you lose.”

Kurt #24

“This is similar to the two coin flip, but reduces the odd of a “do over”. 1) Flip 5 coins at once. 2) If you get 1 head (5/32) or 4 heads (5/32) you win! (10/32 total) 3) If you get 2 heads (10/32) or 3 heads (10/32) you lose. (20/32) 4) If you get 0 heads (1/32) or 5 heads (1/32), do over. (2/32)”

The Stopping Point Solution

From Michael Josephy (#26_1):

“Throw a coin until you throw a tail. One wins if an odd number of heads have been thrown before that tail. So the winning sequences are HT, HHHT, HHHHHT, etc. with probability 1/4+1/16+1/64+… = 1/3 (an infinite geometric sequence).”

A number of readers noticed that you could sum an infinite sequence to get 1/3, and a few had this solution or one just like it. There is some serious power in this approach. Check out LAN’s use of infinite binary to define a game you have a 1/e chance of winning in #50_1.

The 1st Player Advantage Solution

From Paul (#23_1):

“1) Your opponent goes 1st, calls Heads or Tails, and flips the coin. If she’s right, she wins. If she is wrong, it’s your turn.2) Now you call Heads or Tails. Again, if you are right, you win; otherwise, go back to step 1).Because your opponent goes 1st, she is twice as likely to win as you — therefore her probability of winning is 2/3 and your is only 1/3.”

I love the simplicity of this method. All we need is a game that one person is twice as likely to win as their opponent. Noting that the second player half as likely to win on any of their flips as the first player was on their flip just previous means that the second player is half as likely to win period. And that means they have a 1/3 chance of winning the game.

The Better Sequence Solution

From conchis (#15):

“Flip a coin repeatedly until one of two three-coin sequences arises, then there are four pairs of sequences that give a 1/3 chance of winning. Where (x,y) indicates a pair of winning and losing sequences respectively, these are: (HTH,HHT), (HTT,HHT), (THH,TTH), and (THT,TTH).”

The Better Sequence Solution is really a variation of the 1st Player Advantage Solution above. You can read more about this game at the recent Numberplay post.

Heads vs. Tails Solutions

From Marla S (#28): “Start a sequence with a T (by definition–don’t flip). After that, flip the coin repeatedly. If you get two heads in a row BEFORE you get two tails in a row, you win. If you get two tails in a row, you lose. Note that the initialization of the sequence with a tail means that if the first flip is a tail, you lose. Note: this doesn’t quite work if you don’t initialize the sequence with a tail. Also note that this game is equivalent to the first one; it just repeats on HT instead of on TT (which loses).”

I had never seen this solution before, and at first glance, it’s not that clear why it works. Upon examination, though, it could be considered a variation of the 1st Player Advantage Solution. You have twice the chance of losing on flip 2 (by flipping a T) as you do of winning on flip 3 (by flipping a H! Notice that the only way you could get a head on flip 3 is if you already had gotten one on flip 2, which gives you 2 flips in a row). It continues on like this: your chances of winning are half your chances of losing for each pair of consecutive flips, and hence for the whole game.

The Gambling Stopping Point Variation

There’s a wonderful discussion between Jordan Greenblatt and Winston Luo (#32) that boils down to this solution:

“Keep betting $1 on a coin flip, and end if we have either won W or lost L. Because this is a valid strategy, it must have expectation zero, which means that the probability of winning W is L/(W L), and the probability of losing L is W/(W L). (I’ve glossed over a couple details here, but the details are unenlightening.) So we can use our fair coin to play this game with the given strategy, and we can fix the endpoints to give us a win with any rational probability. Then if we let W = 2 and L = 1, it works.”

A few words about this solution. The idea here is quite elegant. Since we don’t have any advantage or disadvantage, our expected outcome is to make $0 on this game. This means that if we broke up our games by stopping after $2 wins or $1 losses, we would expect that for every time we win $2, we should expect to have lost $1 twice; that’s the only way we end up with the $0 we expect to make. But this means that we are twice as likely to lose than to win! This is the territory of the 1st Player Advantage Solution above. The beauty here is that this solution generalizes to help you design games for any rational number, to give you that chance of winning.

Solutions by Symmetry

From Tom Enrico #47:

“My solution is a game you play with two friends. You pass the coin around, each flipping it once per round. If all three flips are heads, or if all three flips are tails, you each flip the coin again. Otherwise, the odd man out wins — that is, you win if you got a head and both of the other players got tails, or if you got a tail and both of the others got heads. Since each player has the same probability of winning, your chance is 1 in 3.”

From Marla S. #28 “Race three markers. Flip the coin once for each marker. If it’s a head, the marker advances. If it’s a tail, it doesn’t. Keep flipping for each marker until one marker is in front of both of the others. At completion, if the first marker is in front, you win. If either of the other two are in front, you lose. You can also play a variation of this where any marker left behind after a round is out and the remaining two race each other. Obviously, if the first marker is out first, you lose.”

These beautiful solutions take advantage of the fact if you play a fair game in a group of three, you have a 1/3 chance of winning. Aside from the elegance, note that these games generalize to any rational probability of winning as well. Say I want a game that I have a 31 out of 73 chance of winning. I’ll race 73 markers using Marla S.’s rules, and mark the first 31 of them with a blue dot. If one of the dotted one ends in front, I win. Lo and behold, my chances of winning are 31/73. I can easily design a similar game that gives any rational probability of my winning.

So there’s our slate of solutions! I thought this was a fantastic discussion, and for those who want to check out the comments, there is a ton more in there, including biased coins, martingales, and computations of expected values of the length of the game.

There were a number of deceptive games put forward that ended up not working for one reason or another. People caught and corrected most of these, but at least one slippery attempt made it through, and that was from Erik Zachte #38.

“Flip the coin until in the last three tosses occurs both a head and a tail. If the side that occurred just once in those three flips came last you win.”

This solution contains a delightful miscalculation that’s so subtle I almost missed it. I consider all mistakes productive, but this one I think is especially so. It taught me a lot about this problem. I’ll leave finding the miscalculation as a parting puzzle.

I have to mention that there were, of course, numerous technically-correct-but-not-quite-in-the-spirit-of-the-problem solutions involving fat coins, drawn markings on the ground, slot machines, dice (bought with coins), striped floors, guessing games, dates on the coin, angles of orientation of the coin, friends and other variables. I won’t catalog them, but one of them made me laugh, and is, on reflection, a pretty good answer to the question. I’ll end with that one, from pris (#27):

“Under my hand I have a coin with a heads facing up, tails facing up, or no coin at all. Which is it? (N.B. I have small children)”

Until next time. Thanks for all the great contributions!

Thank you, Dr. Finkel! And thanks as well to everyone who contributed to this week’s discussion: Neal, Richardo Ech, Steve Kass, Bram Weiser, Larry Johnson, Joshua Zucker, Pummy Kalsi, D-Ferg, Jonathan batchelor, Michael White, Steve Easterbrook, House fan, Ravi, Otto, Robert Grauer, Jay, Kurt, Michael Josephy, pris, Marla S, John, blah, B Rubin, Joe, J E Russell, Jordan Greenblatt, Rob, polymath, Kenneth Berniker, Brian, Erik Zachte, Tully, Kaye Thomas, Paul, Nuffsaid, Sreenadh, Tony, Aaron Carlisle, Corey Luskin, Tom Enrico, conchis, russ, Brent L, sw, John Plotz, msk, LAN, Marlon Field, Duncan Gilles, Tim, c101, jap, Patrick, EEE, Gary, Winston Luo, Hans, Daniel Finkel, Giovanni Ciriani and ralls.

01/01/2021

Somehow I was reminded of the 2012 movie Tenchi: The Samurai Astronomer again. There are not many movies you need watch in a life, and this one should be listed. There are many movies you can watch in a life, and this one should be listed as well.

12/07/2020

Principles of Mathematical Analysis is called “Baby Rudin”, Real and Complex Analysis is called “Papa Rudin” and Functional Analysis is called “Grandpa Rudin”. Second hand book market value rose to high but status usually very poor, no good new prints. Both not good for beginners.

12/04/2020

MathPages is a good problem site. Got to know Bank and Bridge Problem from it.

12/03/2020

Matrix67 started from 2005-07-22 and ended on 2016-10-18. Not all of the posts daily and related to math but it worths a go-through and taking out the math parts.

11/29/2020

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.

Actually, if you want to people know how to build a ship and long for the sea, then you need build a blog first.

11/23/2020

Testing for divisibility by 19

Double the last digit and add the next-to-last. Double that and add the next digit over. Repeat until you’ve added the leftmost digit. The result will be a smaller number which has the same mod-19 residue.

Actually this page and wiki mentions these rules.

11/22/2020

- New Math from Wiki

- A Mathematician’s Lament

11/21/2020

Testing divisibility by 7, 11, and 13

$10^3 \equiv \text{ -1 mod 1001 } \implies \displaystyle \sum_{i=0}^{n}{a_i \cdot 10^{3i}} \equiv \displaystyle \sum_{i=0}^{n}{(-1)^{i}a_i} \text{ mod 1001}$

The heart of the method is that $7 \times 11 \times 13 = 1001$. If I subtract a multiple of 1001 from a number, I don’t change its divisibility by 7, 11, or 13. More than that, I don’t change its remainder by 7, 11, or 13.

11/19/2020

Godel’s Incompleteness Theorems

I found this is a favorite topic to Indians, not sure why.

Interesting Quotes

- Arithmetical truth cannot be defined in arithmetic – Alfred Tarski

- Incompleteness theorem only applies to axiomatic systems, and English language is not an axiomatic system.

References

- Godel’s paper and English translation

- Godel’s Incompleteness Theorems on Stanford

- A Simple Proof of Godel’s Incompleteness Theorems

Wiki

Books

Youtube Videos

- Godel’s 1st Incompleteness Theorem - Proof by Diagonalization

- Kolmogorov Complexity and Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems

- An Intro series with Chinese subtitles - 1 - 2