12/03/2021

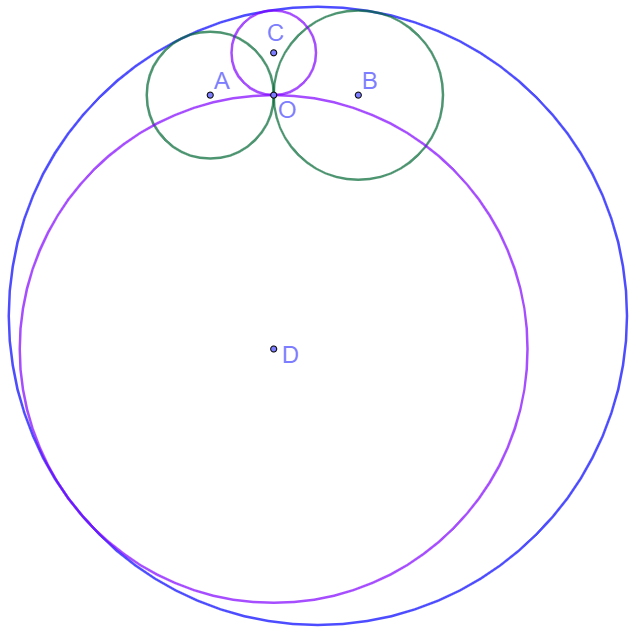

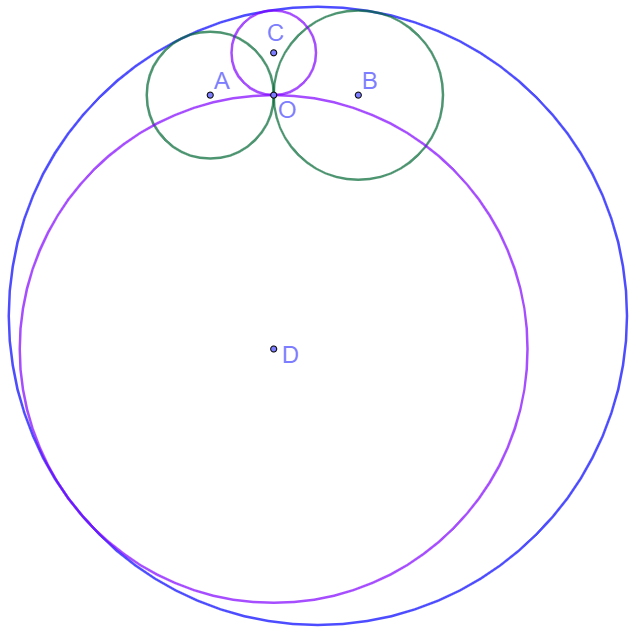

Two green circles are externally tangent and two purple circles are externally tangent at the same point. And all these four circles are internally tangent to a blue circle. The radiuses of the green circles are 3 and 4. The radius of one purple circle is 2. Find the radius of the other purple circle.

Solve:

Let $A, B$ be the centers of two green circles, $C,D$ the centers of two purple circles, $O$ the tangent point. Let circle $O$ be the unit circle centered at $O$. Get the inversions of all the circles:

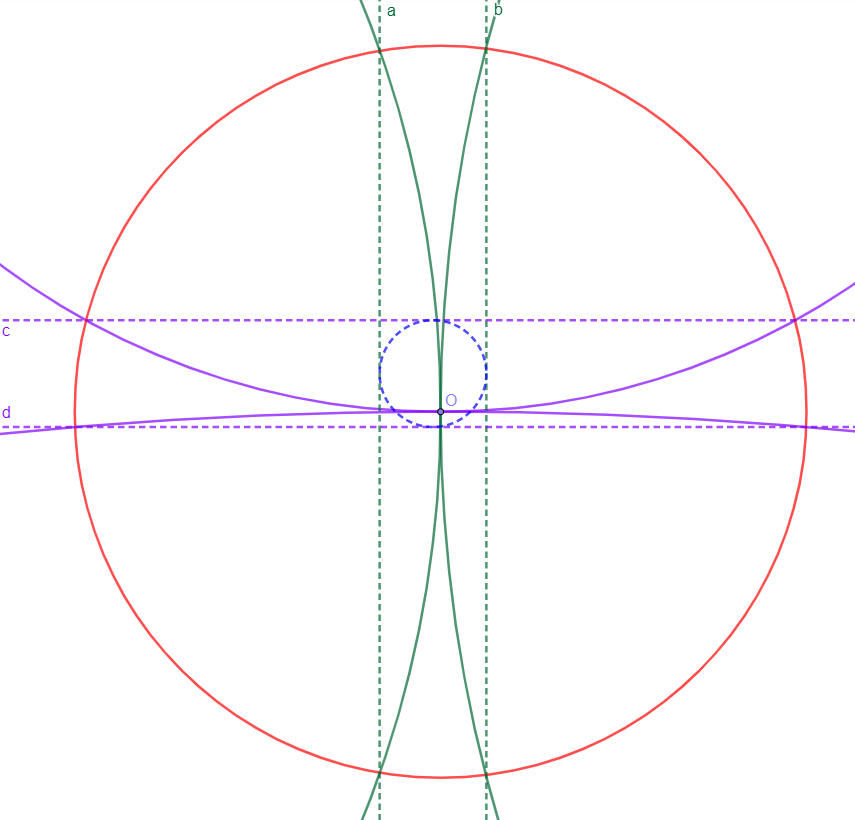

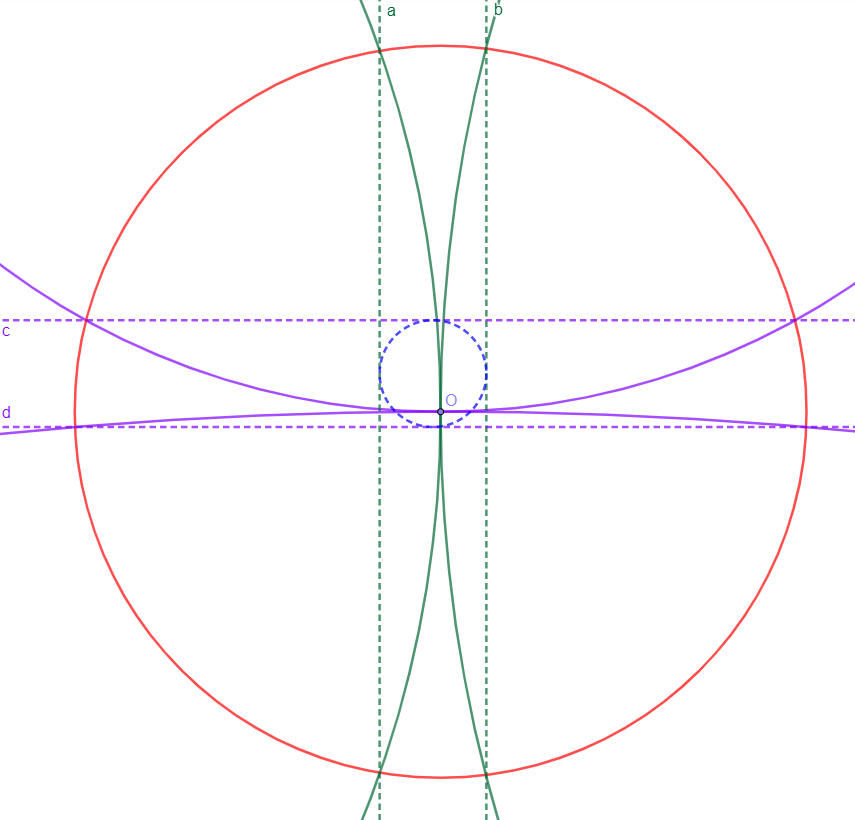

Due to the properties of inversion, the green circles pass through the inversion center $O$, so they are converted to line $a, b$, with distances to $O$ as $\dfrac{1}{2r_A}, \dfrac{1}{2r_B}$ respectively; similarly, the purple circles are converted to line $c,d$ with distances to $O$ as $\dfrac{1}{2r_C}, \dfrac{1}{2r_D}$ respectively. The blue circle does not pass through the inversion center $O$ so it is converted to a circle, still tangent to the mirrors of the four circles, i.e., four lines $a,b,c,d$. So we know that the distance between line $a,b$ is equal to the distance between line $c,d$:

$\dfrac{1}{2r_A}+\dfrac{1}{2r_B}=\dfrac{1}{2r_C}+\dfrac{1}{2r_D} \implies \dfrac{1}{r_A}+\dfrac{1}{r_B}=\dfrac{1}{r_C}+\dfrac{1}{r_D}$

$r_A=3, r_B=4, r_C=2 \implies r_D=\bbox[1px, border: 1px solid black]{12}$

So the radius of the other purple circle is 12.

[中文] 两个相互外切的绿色圆与两个相互外切的紫色圆的切点在同一点,这四个圆与蓝色圆内切。已知绿色圆半径为3和4,其一紫色圆半径为2,求另一紫色圆半径。

解:

设绿色圆圆心$A,B$和紫色圆圆心$C,D$以及切点$O$如上图所示。做以$O$为圆心的单位圆(下图红色圆),对所有五个圆做关于该单位圆的反演变换:

根据反演变换性质易知,绿圆$A,B$经过反演中心$O$,所以它们关于单位圆$O$的像为直线$a,b$,与反演中心$O$的距离分别为$\dfrac{1}{2r_A}, \dfrac{1}{2r_B}$,紫圆$C,D$也经过反演中心$O$,所以它们关于单位圆$O$的像为直线$c,d$,与反演中心的距离分别为$\dfrac{1}{2r_C}, \dfrac{1}{2r_D}$。蓝圆与四圆相切,且不经过反演中心$O$,所以它关于单位圆$O$的像仍然为圆,且与四圆的像相切,即为上图所示虚线蓝圆,可见直线$a,b$的相距与直线$c,d$的相距相等,即

$\dfrac{1}{2r_A}+\dfrac{1}{2r_B}=\dfrac{1}{2r_C}+\dfrac{1}{2r_D} \implies \dfrac{1}{r_A}+\dfrac{1}{r_B}=\dfrac{1}{r_C}+\dfrac{1}{r_D}$

$r_A=3, r_B=4, r_C=2 \implies r_D=\bbox[1px, border: 1px solid black]{12}$

故所求紫色圆半径为12。

12/04/2021

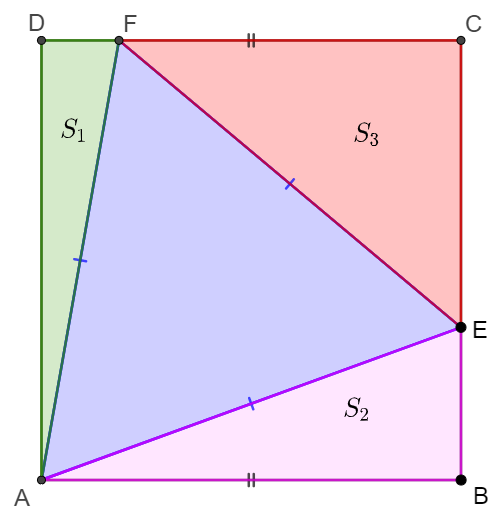

Rectangle $ABCD$ has two points $E, F$ on side $BC, CD$, and $\triangle{AEF}$ is equilateral. Prove $S_{\triangle{CEF}}=S_{\triangle{ADF}}+S_{\triangle{ABE}}$

Prove:

Let $S_{\triangle{AEF}}=S_0, S_{\triangle{ADF}}=S_1, S_{\triangle{ABE}}=S_2, S_{\triangle{CEF}}=S_3$. So we need prove $S_3=S_1+S_2$.

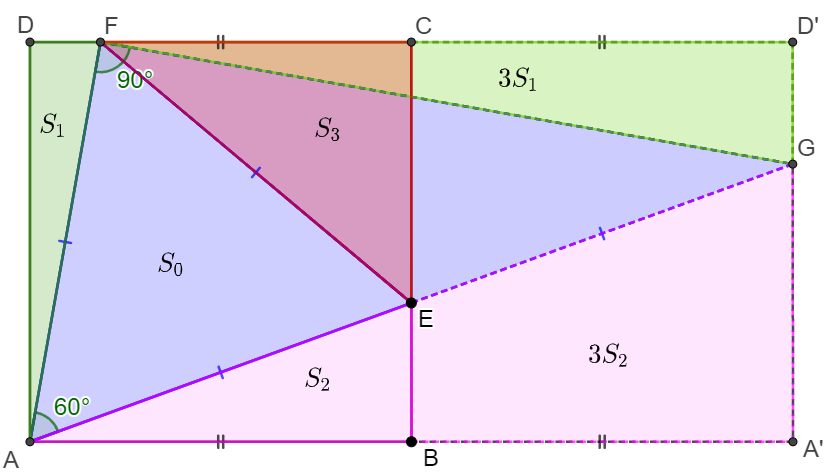

Extend $AB$ to $A’$ so that $AB=BA’$, extend $DC$ to $D’$ so that $DC=CD’$. Extended $AE$ and $A’D’$ intersect at $G$. Connect $FG$.

Easy to see that $AB=BA’ \implies AE=EG \implies S_{\triangle{AEF}}=S_{\triangle{FEG}}=S_0, S_{EBA’G}=3S_{\triangle{ABE}}=3S_2$

$\angle{FAE}=60^{\circ}, AE=EF=AF \implies \angle{EFG}=\angle{AGF}=30^{\circ} \implies \angle{AFG}=90^{\circ}, GF=\sqrt{3}AF $

$\implies \angle{DAF}=\angle{D’FG} \implies S_{\triangle{D’FG}}=3S_{\triangle{ADF}}=3S_1$

$\implies S_{AA’D’D}=2S_{ABCD}=2(S_0+S_1+S_2+S_3)=2S_0+S_1+3S_1+4S_2 \implies S_3=S_1+S_2 \blacksquare$

12/05/2021

Given any five integers, prove that there must be four of them as $a,b,c,d$ so that 28 divides $(a^2-b^2)(c^2-d^2)$

Proof: All integers mod by $7$ we get ${0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}$, so their squares mod by $7$ will be ${0, 1, 4, 9\equiv 2, 16 \equiv 2, 25 \equiv 4, 36 \equiv 1}={0, 1, 2, 4}$.

So pick any $5$ from them will at least have two integers that the difference of their squares is $0$ mod 7. Take them as $a, b$.

All integers mod by $4$ we get $0, 1, 2, 3$, so their squares mod by $4$ will be ${0, 1, 4 \equiv 0, 9 \equiv 1}={0, 1}$. For the rest of the three integers after above step, there must be two of them so that the difference of their squares is $0$ mod 4. Take them as $c, d$.

So there will be $(a^2-b^2)(c^2-d^2) \equiv 0$ mod $28$. $\blacksquare$

12/06/2021

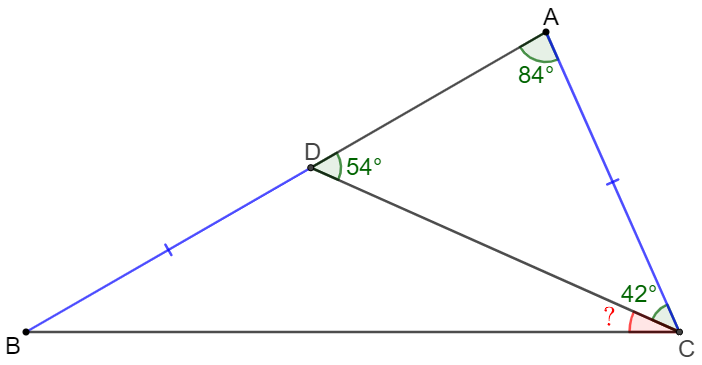

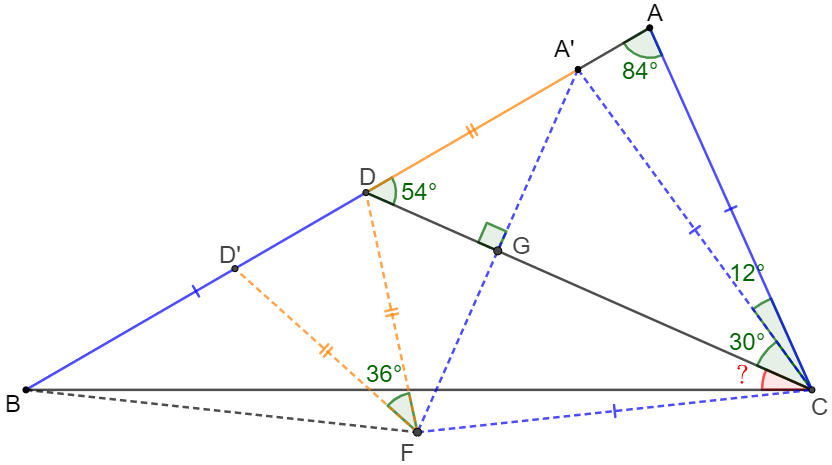

In $\triangle{ACD}, \angle{A}=84^{\circ}, \angle{ACD}=42^{\circ}$. Now extend $AD$ to $B$ so that $AC=BD$. Find $\angle{BCD}$.

Solve 1:

Make $A’$ on $AD$ so that $\angle{ACA’}=12^{\circ} \implies AC=A’C, \angle{A’AC}=84^{\circ}, \angle{ACD}=30^{\circ}$.

Let $E$ be the circumcenter of $\triangle{A’CD} \implies A’E=CE=DE, \angle{CED}=2*\angle{A’AC}=168^{\circ} \implies \angle{EDC}=\angle{ECD}=6^{\circ}$

$\implies \angle{EDA’}=54^{\circ}+6^{\circ}=60^{\circ} \implies \triangle{A’DE}$ is equilateral triangle.

Make equilateral $\triangle{A’CF}$, so that $A’C=CF=A’F=BD$, $A’F$ and $CG$ intersect at $G$. Easy to see that $CG \perp A’F \implies DF=A’D, \angle{DFA’}=\angle{DA’F}=\angle{EA’C}=\angle{ECA’}=36^{\circ}$

Now make $H$ on $A’C$ so that $CE=CH=DE=A’E \implies \angle{CHE}=\angle{CEH}=72^{\circ} \implies \angle{EA’H}=\angle{A’EH}=36^{\circ} \implies A’H=EH$

$\implies \triangle{A’DF} \sim \triangle{A’EC} \implies \dfrac{A’D}{AF}=\dfrac{A’H}{A’E} \implies \dfrac{A’D+AF}{AF}=\dfrac{A’H+A’E}{A’E} \implies \dfrac{A’D+BD}{AC}=\dfrac{A’H+CH}{A’D}$

$\implies \dfrac{A’B}{A’C}=\dfrac{A’C}{A’D}\implies \triangle{A’BC} \sim \triangle{A’CD} \implies \angle{A’BC}=\angle{A’CD}=30^{\circ} \implies \angle{BCD}=54^{\circ}-30^{\circ}=\bbox[5px, border: 1px solid black]{24^{\circ}} $

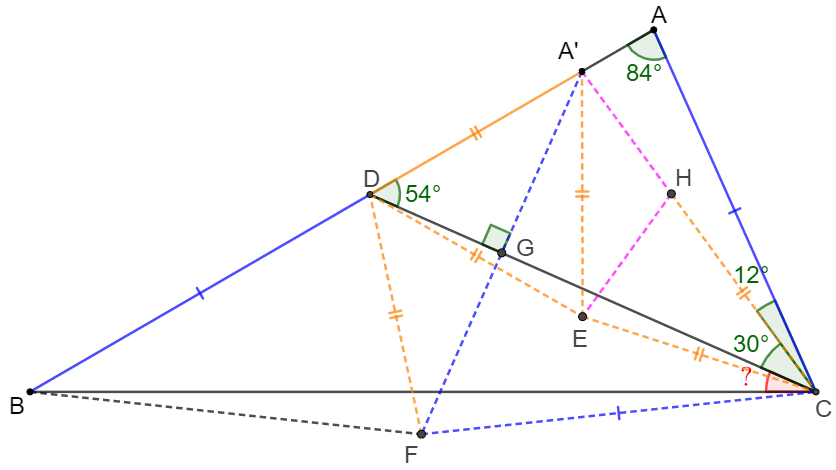

Solve 2:

Make $A’$ on $AD$ so that $\angle{ACA’}=12^{\circ} \implies AC=A’C, \angle{A’AC}=84^{\circ}, \angle{A’CD}=30^{\circ}$.

Make equilateral $\triangle{A’CF}$, so that $A’C=CF=A’F=BD$, $A’F$ and $CG$ intersect at $G$. Easy to see that $CG \perp A’F \implies DF=A’D, \angle{DFA’}=\angle{DA’F}=36^{\circ} \implies \angle{BDF}=72^{\circ}$

Make $D’$ on $BD$ so that $FD’=FD \implies \angle{DD’F}=72^{\circ} \implies \angle{DFD’}=36^{\circ}\implies\angle{AD’F}=\angle{A’FD’}=72^{\circ} $

$\implies A’F=A’D’=AC=BD \implies BD’=A’D=FD=FD’\implies \angle{D’BF}=36^{\circ} \implies \angle{BFD}=\angle{BDF}=72^{\circ} $

$\implies BD=BF=AC=A’C=CF \implies \angle{BFC}=\angle{BFD}+\angle{DFA’}+\angle{A’FC}=168^{\circ}\implies \angle{BCF}=6^{\circ} $

$\implies \angle{BCD}=60^{\circ}-30^{\circ}-6^{\circ}=\bbox[5px, border: 1px solid black]{24^{\circ}}$

12/12/2021

Let $a$, $b$ and $n$ be positive integers such that $n \ge 2$ and $(ab)^{n-1}+1$ divides $a^n+b^n$. Show that $\dfrac{a^n+b^n}{ab^{n-1}+1}$ is a perfect $n^{th}$ power of an integer. i.e., $k=\dfrac{a^n+b^n}{(ab)^{n-1}+1} \in \mathbb{N} \implies \exists c \in \mathbb{N}, k=c^n$. (special case when $n=2$: 1988 IMO Problem 6)

Prove:

(1) When $a=b$:

$k=\dfrac{2a^n}{a^{2n-2}+1} \in \mathbb{N} \implies 2a^n=ka^{2n-2}+k \implies 2=ka^{n-2}+\dfrac{k}{a^n}$

$n\ge2, n \in \mathbb{N}, a \in \mathbb{N}, k \in \mathbb{N} \implies n-2 \ge 1 \implies a^{n-2} \ge 1 \implies ka^{n-2} \ge 1 $

$\implies ka^{n-2}=1, \dfrac{k}{a^n}=1 \implies a^{2n-2}=1 \implies a=b=1, k=1$

(2) When $a \ne b$, WLOG, suppose $a \gt b$

(2.1) When $n=2$

Suppose $k$ is a non-square positive integer and there exist positive integers $(a, b)$ so that $k=\dfrac{a^2+b^2}{ab+1}$. Among these positive integers, suppose $(A, B)$ are the ones satisfying $k=\dfrac{A^2+B^2}{AB+1}$ and such that $A+B$ is minimized, and WLOG, assume $A \gt B$.

Fixing $B$, then $A$ is one root $x_1=A$ of equation $x^2-(kB)x + (B^2-k)=0$. Then we know the other root $x_2$ satisfies $x_2=kB-A$ and $x_2=\dfrac{B^2-k}{A}$.

$x_2=kB-A \implies x_2 \in \mathbb{Z}$. $k$ is not a perfect square and $x_2=\dfrac{B^2-k}{A} \implies x_2 \ne 0$

$\dfrac{x_2^2+B^2}{x_2B+1}=k \gt 0 \implies x_2 \gt 0 \implies x_2 \in \mathbb{N}$

$A \gt B \implies A^2 \gt B^2 \gt B^2-k \implies A \gt \dfrac{B^2-k}{A} $

$\implies x_2=\dfrac{B^2-k}{A} \lt x_1 = A \implies x_2 + B \lt A + B$

This means, with $B$ fixed, we have $x_2$ as a smaller root than $x_1=A$ and we get even smaller $x_2+B \lt A+B$. This contradicts the minimality of $A+B$.

This means $x_2$ can be smaller and smaller until it reaches $0$ and that means $k=B^2$. The original assumption is not correct and $k$ is a perfect square.

(2.2) When $n \gt 2$

We have $n \gt 2, a \gt b, k=\dfrac{a^n+b^n}{(ab)^{n-1}+1}, a,b,k,n \in \mathbb{N} \implies b^n-k=(kb^{n-1}-a)a^{n-1}$

(2.2.1) If $k > b^n$, then $k>k-b^n=a^{n-1}(a-kb^{n-1}) >0 \implies a-kb^{n-1}>0 \implies a-kb^{n-1} \ge 1 $

$\implies k \ge a^{n-1} \implies a>kb^{n-1}\ge k \ge a^{n-1} \implies a > a^{n-1}$ this is not possible

(2.2.2) If $k < b^n$, and since $b<a$ then $kb^{n-1}-a=\dfrac{b^n-k}{a^{n-1}} < \dfrac{b^n}{a^{n-1}} < \dfrac{b^n}{b^{n-1}}=b $

$\implies kb^{n-1}<a+b \implies (k-1)b^{n-1}<a+b-b^{n-1} \le a \implies (k-1)b^{n-1} < a$

and $k<b^n \implies b^n-k=(kb^{n-1}-a)a^{n-1} > 0 \implies kb^{n-1}-a > 0 \implies kb^{n-1}-a \ge 1$

if $k > 1$, then $2 \le k \implies 1 \le k-1 \implies b^{n-1} \le (k-1)b^{n-1} < a \implies b^{n-1}<a $

$\implies b^n-k=(kb^{n-1}-a)a^{n-1} \ge a^{n-1} > (b^{n-1})^{n-1} \ge b^n \implies b^n-k > b^n$ this is not possible, so the only possible situation is $k=1=1^n$ , then the statement is proved true for this case.

(2.2.3) If $k=b^n$ then the statement is proved true for this case as well.

References:

- The case $n=2$ of this problem is mentioned in Vieta Jumping Wiki

- The case $n=2$ of this problem is mentioned in book Problem-Solving Strategies by Arthur Engel, in Chapter 6, E15.

-

The case $n=2$ of this problem is also mentioned in book Modern Olympiad Number Theory by Aditya Khurmi, in Chapter 4, Example 4.7.1.

- Alternative proof that $(a^2+b^2)/(ab+1)$ is a square when it’s an integer

- When is $f(a,b)=\dfrac{a^2+b^2}{1+ab}$ a perfect square rational number?

- AOPS link 1

- AOPS link 2

- AOPS link 3

- What is the algebraic intuition behind Vieta jumping in IMO1988 Problem 6?

- Underlying structure behind the infamous IMO 1988 Problem 6

- When do Pell equation results imply applicability of the “Vieta jumping”-method to a given conic?

- The Legend of Question Six - Numberphile

12/18/2021

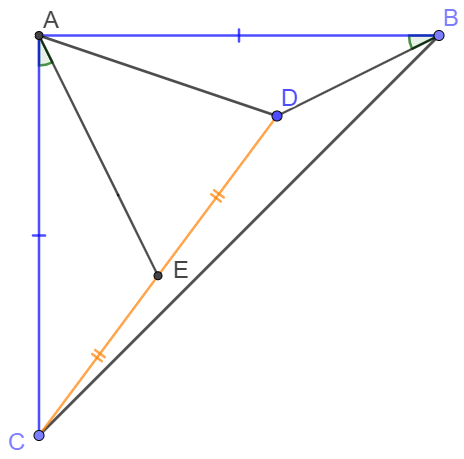

$AB=AC, \angle{CAB}=90^{\circ} \text{ in } \triangle{ABC}$, $D$ is inside $\triangle{ABC}$ and $E$ is the midpoint of $CD$ so that $\angle{CAE}=\angle{ABD}$. Show that $\angle{DAE}=45^{\circ}$.

Prove:

Extend $BD$ so it and $AE$ intersect at $F$. Extend $AE$ to $G$ so that $CG \perp AG$.

$\angle{CAE}+\angle{EAB}=90^{\circ}, \angle{CAE}=\angle{ABD} \implies \angle{ABD}+\angle{EAB}=90^{\circ} \implies AF \perp BF$

$AC=AB, \angle{CAE}=\angle{ABD}, \angle{AGC}=\angle{AFB}=90^{\circ} \implies \triangle{ACG} \cong \triangle{BAF} \implies CG=AF$

$CE=DE, \angle{DFE}=\angle{CGE}=90^{\circ}, \angle{CEG}=\angle{DEF} \implies \triangle{DEF} \cong \triangle{CEG} \implies CG=DF $

$\implies AF=DF \implies \angle{DAE}=45^{\circ}\blacksquare$

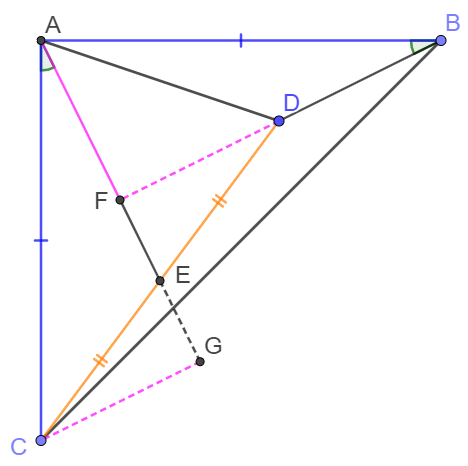

12/20/2021

Find $\angle{BAC}$ in following figure:

Solve:

Connect $EF$:

Easy to see that $AE \perp BD \implies \triangle{DEG} \cong \triangle{BEG} $

$\implies \angle{EBG}=\angle{EDG}=30^{\circ}, DE=BE, DG=BG \implies \triangle{ADG} \cong \triangle{ABG} $

$\implies \angle{BAE}=\angle{DAE}=40^{\circ}=\angle{EDF} \implies ADEF \text{ are cyclic } \implies \angle{AEF}=\angle{ADF}=40^{\circ}$

$\implies AF=EF, \angle{BEF}=\angle{FCE}=20^{\circ} \implies CF=EF, \angle{EFB}=180^{\circ}-20^{\circ}-50^{\circ}-30^{\circ}=80^{\circ} $

$\implies BE=EF=DE=AF=CF \implies AF=CF \implies \angle{CAB}=\dfrac{\angle{CFB}}{2}=\dfrac{60^{\circ}}{2}=\bbox[5px, border: 1px solid black]{30^{\circ}}$

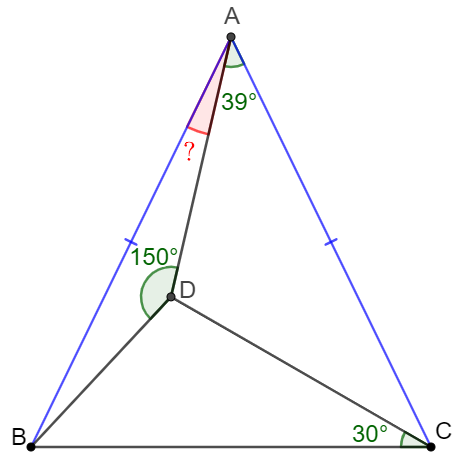

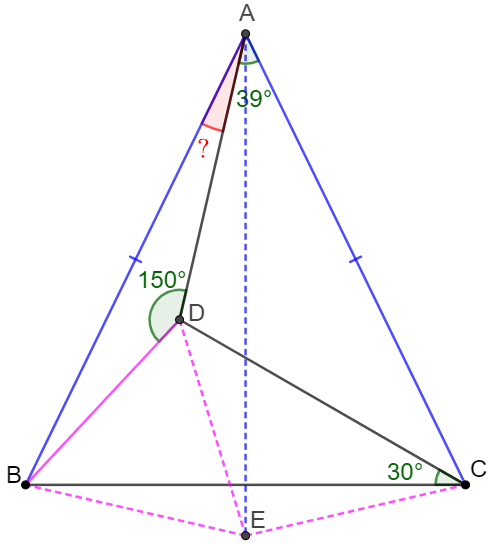

12/28/2021

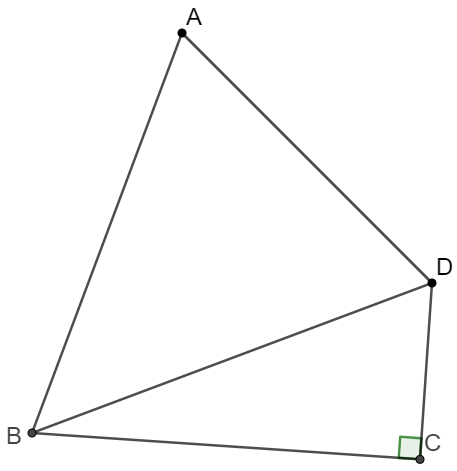

In quadrilateral $ABCD$, $AD=2CD, BC \perp CD, \angle{ADC}=2\angle{A}$. Prove: $AB=BD$

12/29/2021

Solve:

Let $E$ be the circumcenter of $\triangle{BCD}$, easy to see that

$BE=DE=CE, \angle{BEC}=2*\angle{BCD}=60^{\circ} \implies BD=DE, \angle{BDE}=60^{\circ} $

$\implies \angle{ADE}=360^{\circ}-150^{\circ}-60^{\circ}=150^{\circ}=\angle{ADB} \implies \triangle{ABD} \cong \triangle{AED} $

$\implies \angle{BAD}=\angle{EAD}, AB=AE=AC \implies \triangle{ABE} \cong \triangle{ACE} $

$\implies \angle{BAE}=\angle{CAE} \implies \angle{BAD}=\dfrac{\angle{CAD}}{3}=\dfrac{39^{\circ}}{3}=\bbox[1px, border: 1px solid black]{13^{\circ}}$